Where Stories Begin

Not long ago, I was sitting with my young son, telling him a story, when he interrupted me to ask, “Where did that story come from?”

“I just thought of it,” I said.

He was not satisfied. “But where did it come from?”

“From my imagination,” I said.

“Where’s your magic nation?”

“In my mind,” I said.

Oscar’s question is a variation of the same one I heard again and again from graduate students during my years teaching creative writing, the same question I hear every time I do a reading or visit a book club: where do stories begin?

I imagine every writer would have a different answer. For most, it involves some kind of percolation. Something occurs to you in the shower, or during a walk, or while down in the garage doing laundry. Days later, or weeks or months later, that original idea surfaces in the mind, and something else is layered on top of it. If the idea seems urgent enough, you get yourself to the notebook or the computer and write it down. It is possible to go for months of creative drought, but I’ve learned not to get too discouraged. Humans are born storytellers. I always trust that something will come; eventually, I’ll find my story.

When I’m feeling particularly uninspired, I try to find something mind-blowing to read. Sometimes, if I am very fortunate, I happen upon a book or essay that jogs my imagination, something that loosens the rust around the synapses and gets a story moving.

A couple of years ago, I was about fifty pages into the novel that would become No One You Know. I had a basic plot, and a melange of ideas around which to construct the story. I knew, for example, that I was interested in the fine line between fact and fiction, the way stories shape our lives. I knew that I wanted to capture the spirit of San Francisco, my adopted home. I knew that the story would be told by Ellie Enderlin, a coffee buyer in her mid-thirties who had lost her sister Lila–a math prodigy at Stanford–to violent crime twenty years before. Lila’s murder was sensationalized in a true crime book written by Ellie’s English professor, whose version of events derailed the life and career of a mathematician named Peter McConnell, with whom Lila had been working to solve a centuries-old mathematical puzzle.

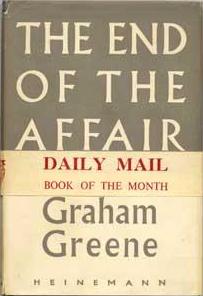

During this time, I had lunch in North Beach with a writer friend and teaching colleague–Juvenal Acosta. We got to talking about our favorite books. Juvenal had high praise for Graham Green’s The End of the Affair

During this time, I had lunch in North Beach with a writer friend and teaching colleague–Juvenal Acosta. We got to talking about our favorite books. Juvenal had high praise for Graham Green’s The End of the Affair![]() , and couldn’t believe I’d never read it. I went right out and checked the book out from the library; six months later it was still sitting in my office, full of post-it notes. Eventually I returned it, paid the fine, and bought my own copy. It is one of the most bedraggled books I own. Bedragglement is evidence of a book’s high standing in a person’s life. A book that has been well-loved bears the marks.

, and couldn’t believe I’d never read it. I went right out and checked the book out from the library; six months later it was still sitting in my office, full of post-it notes. Eventually I returned it, paid the fine, and bought my own copy. It is one of the most bedraggled books I own. Bedragglement is evidence of a book’s high standing in a person’s life. A book that has been well-loved bears the marks.

The End of the Affair is the story of a love affair gone wrong, with the mystery of the beloved’s death front and center, but it’s also a book about writing, about finding one’s story and figuring out the best way to tell it.

Like most novels, No One You Know grew out of several ideas that had been percolating over a period of time. But ultimately, it was The End of the Affair that provided the opening impulse for the book. Greene’s novel begins with the line, “A story has no beginning and no end. Arbitrarily one chooses the moment from which to look back or from which to look ahead.” Twenty years after the tragedy that has defined her life, Ellie must decide for herself, as we all must, where her story truly begins.

Purchase The End of the Affair![]() . Purchase Our Man in Havana

. Purchase Our Man in Havana![]() .

.

.

This post originally appeared in 2009 on my blog, Sans Serif.