Anyone who tells you that writing a novel is easy has probably never written one. Here are the five most common statements I hear from people who are struggling to write a novel:

- I don’t know where to begin.

- I’ve written a few chapters, but I can’t figure out where to go from here.

- I have a great idea for a novel, but the idea of actually sitting down and writing it feels too daunting.

- I’ve heard you’re supposed to write an outline for your novel, so I did. Now what?

- I’ve actually written a novel before, but I put it away because it isn’t good enough to send out.

No magic formula.

If you find yourself nodding your head to any of these statements, I know what you’re going through. I’ve been there. The truth is, there’s no magic formula for writing a novel. Writing a novel comes with no guarantee of publication, of success, of sales, of an audience. But if you’re reading this email, you probably know all that already. And I believe that you’ve already made up your mind about one thing: writing a novel is worth the time and effort, the headaches, the inevitable state of not knowing what will happen to the book into which you’ve poured your heart and soul.

You don’t have to know where you’re going.

Too often, novels don’t get written because writers think they have to know exactly where the novel is going before they begin. I worked on my breakout novel, The Year of Fog, for more than a year before I knew what would happen to the child who was kidnapped in chapter one. A year! Most of the how-to books on novel writing will tell you to sit down and write an outline first, and start writing your novel later. My approach is the opposite. There actually will come a time to write an outline, but not until you’re deep into the book, with some key chapters and scenes already written.

Try this:

While I’ve never found a formula for writing, what I have found is a process. It works for me. It has worked for many of my students.

Here are the 4 basic principles.

1.Get some stuff on the page. Write a few key scenes, and fill them with significant detail. Don’t write what you know, necessarily, but write what you care about.

2.Figure out who your characters are and what makes them tick.

3.Put it all together using a process of arrangement that involves your primary story arc, at least one subplot, and thematic associations that add depth and interest to your story.

4.Revise the novel using a revision checklist. Make sure the first 50 pages will catch the attention of one (or all) of these three key people: agent, publisher, reader. Send it out.

I call this process The Paperclip Method.

What’s different about The Paperclip Method is that it doesn’t ask you to know what your story means or where it goes when you begin. It is, instead, a highly intuitive process that requires you to simply enjoy the writing first, and make the tough decisions about what goes where later. Sounds like procrastination, but it’s really about discovery. So often, when working with private clients, I’ll praise a particular section of the book for its naturalness, for the fluidity of the writing and the complexity of the characters. Often, the surprised writer will say, “But that was one of the easiest chapters to write!”

Letting go of the inner tension

I think what’s happened in these sections is that the writer has let go of the inner tension of trying to make the passage fit into a predefined idea, and has, instead, written about what mattered to them in the story.

Forget you’re writing a novel.

So, if you’ve been holding back on your novel because it scared you, or because you got stuck, or because you simply didn’t know where to go, my primary advice would be to forget for a moment that you’re writing a novel.

Instead, begin here:

“I want to write this story because…”

Follow that up with:

“I care about these characters because…”

Then, see where it takes you! You might be surprised.

Learn more about writing your novel with The Paperclip Method.

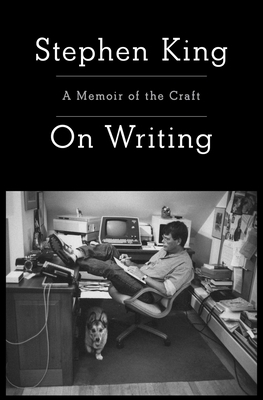

Stephen King recently sat down with Jessica Lahey of The Atlantic Monthly to talk about teaching writing. King’s On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft is one of my favorite books on writing ever written. I love it for its accessibility, its wisdom, its lucidity, and its utter lack of pretension.

Stephen King recently sat down with Jessica Lahey of The Atlantic Monthly to talk about teaching writing. King’s On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft is one of my favorite books on writing ever written. I love it for its accessibility, its wisdom, its lucidity, and its utter lack of pretension.

In 1921,

In 1921,