A stark reminder of how expensive it is to be poor

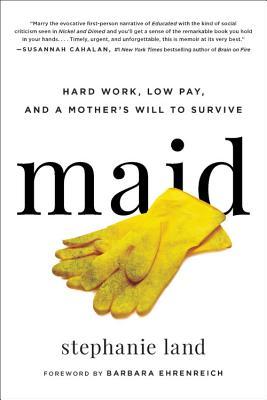

Maid: Hard Work, Low Pay, and a Mother’s Will to Survive, by Stephanie Land, is an eye-opening look at a sadly common type of poverty: the poverty experienced by people who are working too many hours for too little pay while raising children without adequate child care. Despite being educated and, at points in her youth, ambitious, the author falls into poverty after leaving the emotionally abusive father of her child. In Maid, Land provides an unabashed look at how difficult, exhausting, and time-consuming it is to be poor, and at the outrageous expectations our current system puts on those struggling with poverty.

While caring for her infant daughter and working jobs in landscaping and housekeeping, Land must also meet with social workers, fill out complicated forms, and submit evidence to prove that she is poor enough to qualify for services. She must also cope with the disdain of strangers who see her poverty as a kind of moral shortcoming. Through it all, she must manage to put gas in her car and get to and from work, and try to be a good mother, even though she is often hungry.

I grew up only a couple of notches above this kind of poverty, in a home with two educated parents who worked full-time, and remember well the stress that constant financial insecurity put on my parents and our family. My sisters and I were left with child care providers my mother would rather not leave us with, because there were no other options. I remember drinking powdered milk and eating ketchup-and-mayonnaise sandwiches. As I child, I hated the powdered milk but liked the sandwiches, and I thought we ate them because we liked them, although in hindsight I realize there were probably some days when that was all we could afford.

I remember watching my mother begging the repo man (yes, he’s a thing) not to take our car from the driveway, because if he took the car she could not get to her night shift at the hospital. I remember what it is like to be a college student, taking a full load of classes in addition to doing a 20-hour-per-week work study job, with two dollars left to feed myself for the next three days, and rationing those two dollars out with one large bag of potato chips per day, my sole sustenance until I got paid again. I remember my mother’s relief one year during college, when my older sister and I got summer jobs as camp counselors, because she had worried if we came home for the summer, there wouldn’t be enough food. I also remember the disgust with which my own parents viewed people who accepted food stamps, even though a single illness that prevented one of my parents from working when their children were small could have pushed us over the line to needing food stamps ourselves.

Later, as an adult, after many waitressing jobs and after working my way up through the system–a privilege I enjoyed in no small part because I had the benefit of an education–I lived in an upscale community where well-educated stay-at-home moms with exceptional child care providers, housecleaners, and complete financial stability often complained about how “busy” they were without any sense of irony. These were compassionate women who volunteered for social causes and gave a great deal to their community, but who sometimes had blinders when it came to acknowledging the extreme benefit of their economic privilege. Distanced by two decades from my own poverty, I too am guilty of falling into this trap. I too have gone through periods when my own problems seemed bigger than they were, because I had forgotten what it was like to be desperate for the next paycheck.

Maid is a reminder that while, for many of us, fifty dollars may be nothing, for someone else who works brutal hours in physically and mentally exhausting jobs, fifty dollars may be the difference between shelter and homelessness. Even twenty dollars may mean they can feed their children enough calories that week to protect them from hunger. Five dollars may mean they can buy gas or a bus ticket to get to work, and three dollars may mean they can afford fast food or a snack to get them through the day. It is also a reminder that an enormous segment of the poor population works much harder than the rest of us, for far less pay.

Maid is a must-read for any middle class and upper middle class Americans who still believe that the the majority of the poor are poor because they don’t work hard enough. As J.D. Vance points out in his arresting memoir of Appalachia, Hillbilly Elegy, there are poor people who don’t last long on the job or who spend what they do have on all the wrong things. But it is too easy to assume the majority of the poor fit that description, when many are locked in a cycle of working paycheck to paycheck, going further into debt every month and every year because poverty is an expensive way of life. If you can’t pay the rent or put gas in the car or hire a babysitter, if everything takes longer because you have to take public transportation, if you can’t go to college or take the time to find a better job, it becomes outrageously difficult to break the cycle of poverty.

The fact is, it often takes far more time and back-breaking effort to live in poverty than it does to live in comfort. The poor can’t take a day off when their children are sick, and they can’t get a loan to start a business, and they can’t buy a house that will increase in value, and they can’t save for a rainy day. Maid shines a much-needed light on the harsh, day-to-day realities of poverty in America.

Thanks to Hachette Books and Netgalley for providing a review copy of this book.